Our Story

History

The Spalding Gentlemen’s Society, one of the oldest learned societies in the Kingdom and the earliest provincial association for the encouragement of antiquarianism, was founded by Maurice Johnson (1688-1755), “The Antiquary”, of Ayscoughfee Hall, Spalding.

It began with a series of informal meetings of a few local gentlemen at a coffee-house in the Abbey Yard, Spalding, in 1710 to discuss local antiquities and to read The Tatler, a newly published London periodical. In 1712 it was decided to place these meetings upon a permanent footing and proposals were issued for the establishing of “a Society of Gentlemen, for the supporting of mutual benevolence, and their improvement in the liberal sciences and in polite learning”. In that year formal meetings began with the appointment of officers and the keeping in minutes. The founder, Maurice Johnson, also played a leading part in refounding the Society of Antiquaries of London, and for some years an exchange of minutes took place. Francis, Duke of Buccleuch (1695-1751), Lord of the Manor of Spalding-cum-Membris, became Patron of the Society in 1732.

The history of the foundation of the Society and its development in the 18th century is to be found in Nichols’ Bibliotheca Topographica Britannica, 1790, and also in Nichols’ Literary Anecdotes, vol. vi. 1812. Other histories are by the Revd. William Moore, D.D. (1851), Dr. Marten Perry, G.W. Bailey and S.W.Woodward. In 1981 the Lincoln Record Society published The Minute books of the Spalding Gentlemen’s Society 1712-1755 selected and introduced by Dorothy M. Owen, M.B.E., D.Litt.

Women and the Spalding Gentlemen’s Society

For almost 300 years of its history, the Spalding Gentlemen’s Society was a male preserve, as its name suggests. From time to time, its rules officially excluded female members, though occasionally the presence of women was permitted. Times have changed, however, and 2017 celebrates the tenth anniversary of the admission of women as Society members.

Women were not always without background influence, however. Soon after the Society’s foundation in 1710, one of its main activities was subscribing to buy the latest books, then a very expensive item. A letter from an early member suggests including ‘the Ladies’ in this subscription scheme. In 1730, a generous donation of books by Mary Deacon of Peterborough, was recorded. By 1733, the Society’s founder, Spalding lawyer Maurice Johnson, had plans to include ‘female members’ as he wrote to his friend and fellow-member William Stukeley. Though this, like others of Johnson’s ambitious plans, came to nothing, the ladies were invited to the Society’s annual anniversary concert, where wine, tea and coffee were offered to them. His wife and daughters assisted with the Society’s collections and with creating illustrations for the minute books.

The more open social atmosphere of England after the Napoleonic Wars influenced the Society; in 1814 its new rules officially allowed lady members, though they were not to vote on Society matters. This was not to last, and the Victorian Society, reacting against the efforts of the Suffragettes, decided to exclude women again, though they could attend on special occasions as members’ guests. In 1909 they outnumbered the men at a lecture on the French Napoleonic prisoners of war at Norman Cross.

This was still the case when the Society’s splendid new buildings were opened in 1911; the gentlemen had a splendid banquet, while the ladies, who were not present, were thanked for decorating the tables! The twentieth century saw a much more active background presence by women; in the 1930s a woman, Ivy Barrett, created the library’s card index. Although a motion to admit women in 1946 was defeated, female researchers were using the Society’s books and papers. In 1971, five notable female local historians were created Fellows of the Society in acknowledgement of their work, though this still did not confer membership. Women began to assist the Librarian in the care of the Society’s extensive library.

This was the situation when the twenty-first century began, but pressure for greater openness in organisations soon led to a remarkable opening up of the Society. More public Open Days were created, proving very popular; the winter lecture programme moved to the Grammar School and was opened to the general public. Finally, in 2006 a historic vote was taken to admit women as members of the Society.

The first women joined in 2007 and were soon taking an active part in the Society’s activities, becoming officers and helping with the extensive collections in the Museum. Today’s the Spalding Gentlemen’s Society membership is open to everyone aged 18 and over. The broad membership undertake a wide programme of varied activities in lectures and the care of its fascinating museum and archives. Its early founders would have been pleased to see their forward-looking schemes put into action.

Maurice Johnson (1688-1755) was a very remarkable man, responsible for creating the Society and supporting it for over forty years. He brought it from small beginnings, as a group of like-minded friends meeting at a Spalding coffee-house, to a society known across England and beyond as the Spalding Gentlemen’s Society, with corresponding members across the world.

Maurice was the son of a Lincolnshire lawyer, also called Maurice Johnson, who lived at Ayscoughfee Hall and administered legal affairs for local residents and landowners, including managing the Spalding property of the Duchess of Buccleuch. When the Duchess’s grandson, Francis Scott, was about to go to Eton to study, he was accompanied by the young Maurice Johnson who had already received a firm foundation in the Classics at Spalding Grammar School. From there Johnson began his legal studies at the Inner Temple, London, in 1705, qualifying as a barrister in 1710.

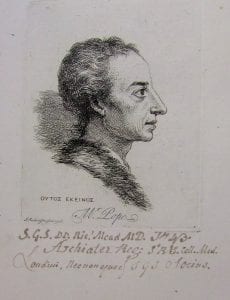

While in London, he took part in the city’s literary life by attending the coffee-house clubs which were a feature of the London scene, meeting weekly to discuss books and philosophical ideas. He was introduced to famous figures like the poet Alexander Pope and the essayists Addison and Steele. It was Richard Steele who encouraged the young Johnson to start a society of his own when he returned to Spalding on qualification, to join the family legal practice.

In 1710 his society began informally as a group of local gentlemen, lawyers, clergy, merchants and doctors, meeting weekly to read and discuss the latest journals like the Tatler and Spectator. By 1712 the group had taken on the task of cataloguing and preserving the Spalding Parish Library. It was given a formal constitution as the Spalding Gentlemen’s Society, with a set of rules permitting the discussion and investigation of the whole area of the arts and sciences, though with an absolute prohibition on discussing politics. This was one factor that kept the Society together when other local groups declined into argument. A further factor was Johnson’s hard work in finding topics for the weekly meetings.

Johnson’s work as a lawyer, specialising in land drainage law, a key area in the 18th-century Fens, took him regularly to London. There, together with friends such as local doctor William Stukeley and the Gale brothers, Roger and Samuel, all of whom became Spalding society members, he helped in 1717 to re-establish the Antiquarian Society, today’s Society of Antiquaries. He also had the opportunity to meet important people of the time and encourage them to become corresponding members of the Spalding Gentlemen’s Society, who could send letters on topics of interest and the latest research, to enliven the Spalding meetings, or honorary members who gave lustre to the Society. These included fellow Lincolnshire man Sir Isaac Newton, Alexander Pope, John Gay, the author of the highly successful Beggar’s Opera, scholars from the universities and Sir John Clerk, the Scottish antiquarian and politician famous for organising the finance of the Act of Union of 1707. An unusual member was Job Diallo, an Islamic prince and scholar from West Africa, who had been taken as a slave to America, was ransomed in 1733 and became a great social success in England on his way home to Africa.

To become a member, one had to donate a book of the value of at least £1 to the Society’s growing library; these books still exist in today’s Society, each inscribed with the donor’s name. Local members also paid a subscription of sixpence for each meeting attended. The Society also established a herb garden to grow unusual and useful plants and a museum containing specimens of natural history, coins and other archaeological finds, together with their growing collection of scientific instruments such as telescopes and microscopes.

The six volumes of minutes of their meetings, kept by Johnson as Secretary, demonstrate the remarkable range of the Society’s activities. There are entries on astronomy, fossils, archæological items such as bronze and stone weapons, the latest poetry, art, philosophical ideas and discoveries in natural history, often accompanied by precise drawings by Johnson, himself a competent artist. Many meetings were enlivened by the reading of letters from the Society’s many corresponding members who lived across Britain and as far afield as Norway, the Caribbean and India. Over 500 of these survive in the modern Society’s archive.

For 45 years Johnson was the central figure of the Society. At the same time he and his wife Elizabeth established a family at Ayscoughfee Hall; of the 25 children born to them, eleven reached maturity. The sons, who had careers in the army, law, church, navy and Indian civil service, became supportive members of the Society and at least one of his daughters provided some illustrations for the Minute Books. Perhaps Johnson’s greatest talent was for friendship. He encouraged people to meet and discuss on a friendly basis and to share their discoveries with other groups including the Royal Society and the Antiquarian Society. His Spalding society produced two other local groups: the Peterborough Gentlemen’s Society, founded in 1730 by the Revd Timothy Neve, former Treasurer of the Spalding society, which survived until the late19th century, and the shorter-lived Brasen Nose Society at Stamford in the late1730s, founded by Johnson’s old friend William Stukeley.

Johnson’s final benefaction to the Society was a way of ensuring its survival. In his will, proved on 30 May 1755, he left the income of “the Chapell at Wykeham in the Parish of aforesaid Spalding” to the Governors of Spalding Grammar School, to be paid to the school’s Headmaster in addition to his salary, to ensure that he “will conscientiously constantly and honestly take charge and care of the Museum Books Papers…of and belonging to the Spalding Gentlemen’s Society”. This arrangement lasted well into the 20th century. Thus the survival of the Society’s library, and with it the continuing existence of England’s oldest surviving provincial learned society, were assured into the 21st century, thanks to the foresight of its remarkable Founder.

Early members included a number of notable eighteenth century figures, among them Sir Isaac Newton, Sir Hans Sloane (President of the Royal Societywhose museum and library formed the nucleus of the British Museum), Alexander Pope (whose Windsor Forest was read in manuscript to the Society), George Vertue (engraver), Dr. William Stukeley, John Anstis F.R.S. Garter King of Arms, John Gay (poet), the Revd. Richard Bentley D.D., Capt. John Perry (engineer), Samuel Wesley, Sir Edward Bellamy (Lord Mayor of London 1735) and Lord Coleraine (President of the Society of Antiquaries).

Later, long after the founder’s death, we find as members Sir Joseph Banks, Sir G. Gilbert Scott, Lord Tennyson, Pishey Thompson (historian of Boston), Lord Curzon of Kedleston (who restored Tattershall Castle and bequeathed it to the National Trust), Lord Peckover of Wisbech and Lord Ancaster (the Society’s Patron from 1960 to 1983).

The present museum in Broad Street was opened in 1911. The erection of this building was rendered possible by the generosity of members and a special bi-centenary appeal. The architect was Joseph Boothroyd Corby of Stamford. Additions were made in 1925 and again in 1960.

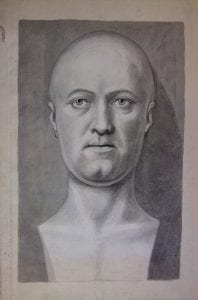

The carved panels on the exterior represent the work of Jules Tuerlinckx of Mailines, a Belgian refugee, resident in Spalding during the First World War. The carvings are from designs made by E.M.M. Smith (1843-1920), the Society’s Honorary Operator (Curator). These panels consist of the arms of the founder over the library window, and above the entrance door a very elaborate carving based on the Society’s book plate. On either side of this are two small panels bearing the monogram “S.G.S.”. The three remaining panels bear the words Art, Literature and Science, indicative of the objects for which the Society was founded. The head carved in the roundel over the front door is that of Edward Gentle (1832-1910), a member who contributed largely towards the cost of the building.

The carved panels on the exterior represent the work of Jules Tuerlinckx of Mailines, a Belgian refugee, resident in Spalding during the First World War. The carvings are from designs made by E.M.M. Smith (1843-1920), the Society’s Honorary Operator (Curator). These panels consist of the arms of the founder over the library window, and above the entrance door a very elaborate carving based on the Society’s book plate. On either side of this are two small panels bearing the monogram “S.G.S.”. The three remaining panels bear the words Art, Literature and Science, indicative of the objects for which the Society was founded. The head carved in the roundel over the front door is that of Edward Gentle (1832-1910), a member who contributed largely towards the cost of the building.

The 18th century sundial on the wall of the caretaker’s residence next door was formerly on the street wall of the Crane Inn in Double Street, Spalding. It was moved from there and erected on its present site in 1913. The weathervane erected on the roof of the museum in 1996 is from the former Ship warehouse in Double Street. It can be seen in the engraving of Spalding High Bridge published by Hilkiah Burgess in 1823.